The story of Marvin Haynes is also the story of Harry Sherer — a 55-year-old mentally disabled man who lived a few blocks from his family’s flower shop who everyone called by his nickname, Randy. Most days, Randy walked to the shop to sit and talk to his brother and sister, to tidy up and smoke cigarettes, eat McMuffins, greet customers.

On May 16, 2004, someone shot Randy in the midst of a botched robbery attempt. According to his sister and sole witness to his killing, the shooter said he was looking for cash he thought was hidden in the flower shop. The neighborhood rumor, possibly founded on some truth, was that the shop’s owner was involved in high stakes gambling and maybe even ran gambling operations out of the shop’s back rooms.

In the end, the shooter left with nothing after firing a bullet that punctured Randy’s rib cage and entered his lung in two places — the aorta and the trachea — exiting the right side of his chest and quickly ending his life from loss of blood. One of the first officers on the scene wrote in his report that “blood from the victim extends from his body all the way back through [the] hallway.” Two discharged and deformed .38 caliber bullets that had entered and exited Randy’s body were recovered by police from the scene.

A subsequent autopsy revealed that Randy suffered from diabetes and severe coronary artery disease, a narrowing of the blood vessels that supply the heart with blood and oxygen. “If he had been a person who did not have these injuries to explain his death,” the medical examiner who performed the autopsy testified at trial, referring to the bullet wounds, “the amount of disease that he had to those vessels would be consistent with somebody dying suddenly and unexpectedly.”

Rev. Albert Gallmon Jr., Pastor of the Fellowship Ministry Baptist Church, remembers Randy from the neighborhood. “He was a dear soul,” Gallmon told Unicorn Riot. “I would go up there to order flowers or just walk around. He was a gentle soul, a very nice guy. He and I would just talk about anything in general from what I can remember and I was very, very disheartened when he was killed.”

Randy Sherer was a man nearing the end of a quiet life. He was loved by his family, who said he enjoyed watching the Timberwolves and playing golf, although he wasn’t very good at it. Marvin Haynes was a 16-year-old kid who liked to smoke a little weed, hang out with his friends, and try to dress nice and get girls. The two couldn’t have been more different. The only thing linking their fates was a neighborhood — Northside Minneapolis.

[Randy Sherer (L) pictured before he was killed in 2004. Marvin Haynes (R) pictured at 16 years old after being charged with Sherer’s murder. Haynes has maintained his innocence ever since.]

Read The Case of Marvin Haynes – Part One

When Mannie Sherer got back from the war in the Pacific, he got a job in wholesale imports. He unpacked boxes of flowers and novelty items until, in 1948, he had saved enough to open his own wholesale flower shop.

He’d returned home to find Minneapolis in the midst of a post-war economic feeding frenzy. America had emerged from the Second World War a global player, pulled out of the Depression on the industries of war and centralized economic planning, which benefited a generation of young, white men like Mannie. The GI Bill and New Deal programs — a brand of democratic socialism the country would never again tolerate — infused the white working class with the capital they needed to start businesses, go to school, buy houses, and start families.

Sherer opened a flower shop at 802 NE Marshall St., on the east side of the Mississippi River, selling flowers at wholesale prices and undercutting the competition. When other florists were selling a dozen roses for $40, “we were probably selling them for $18 or $20,” said Mannie’s son Warren, shortly after his father’s death. “We were probably half the price of the bigger florists.”

In 1961, the elder Sherer moved the business across the river, opening a location at the corner of 33rd Avenue North and Lyndale Avenue North in the McKinley neighborhood on the Northside of Minneapolis. When one of his children, Jerry, was ready to go into business with him, they repainted the sign out front, calling the new store “Mannie’s and Jerry’s Flower Shop.”

What Mannie Sherer didn’t know when he moved his business just a few miles to the west, into Northside Minneapolis, was that he had settled in a neighborhood slated for abandonment and disinvestment by those in power.

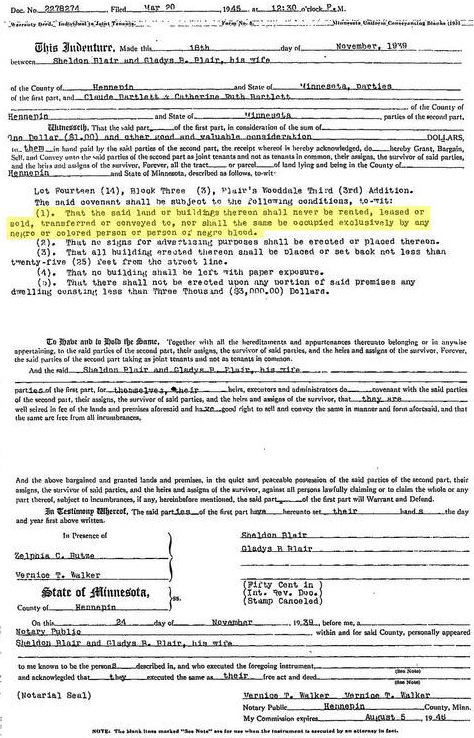

The Northside of Minneapolis had long been a hub for marginalized people unwelcome elsewhere in the city. Beginning in the 1920s, racial housing covenants kept Black, Asian and sometimes Jewish people from owning land in most of the city, inscribing into deeds the restriction that the “premises shall not at any time be conveyed, mortgaged or leased to any person or persons of Chinese, Japanese, Moorish, Turkish, Negro, Mongolian or African blood or descent.” By the 1930s, the majority of deeds in the city of Minneapolis contained these racial housing covenants.

The covenants pushed the majority of Minneapolis’ Black population to the north — from the Camden neighborhood down to Near North — where such covenants were mostly nonexistent. In the mid-60s, when the pressures of segregation and violent policing in Minneapolis approached the breaking point, the Northside was the epicenter of the city’s movements for liberation.

“How many Negroes do you see working on Plymouth Ave?” asked one Black Northside resident in 1966, referring to the Northside business district, “We can’t [get] jobs there. Everywhere we look for work they tell us we’re not qualified. All we are qualified for is to wash dishes for $1.25 an hour.”

Increasingly, Black Northsiders inspired by the Civil Rights Movement spreading throughout the country, but disillusioned by its limitations, began to organize themselves to push for more substantive change. On May 16, 1967, Black militant and Black Power advocate Stokely Carmichael (who later changed his name to Kwame Toure) spoke at Williams Arena at the University of Minnesota, addressing a crowd of 7,000. Meanwhile, the FBI was monitoring the activities of a group of Black Northsiders whose home, according to their reports, was “Black Power headquarters.”

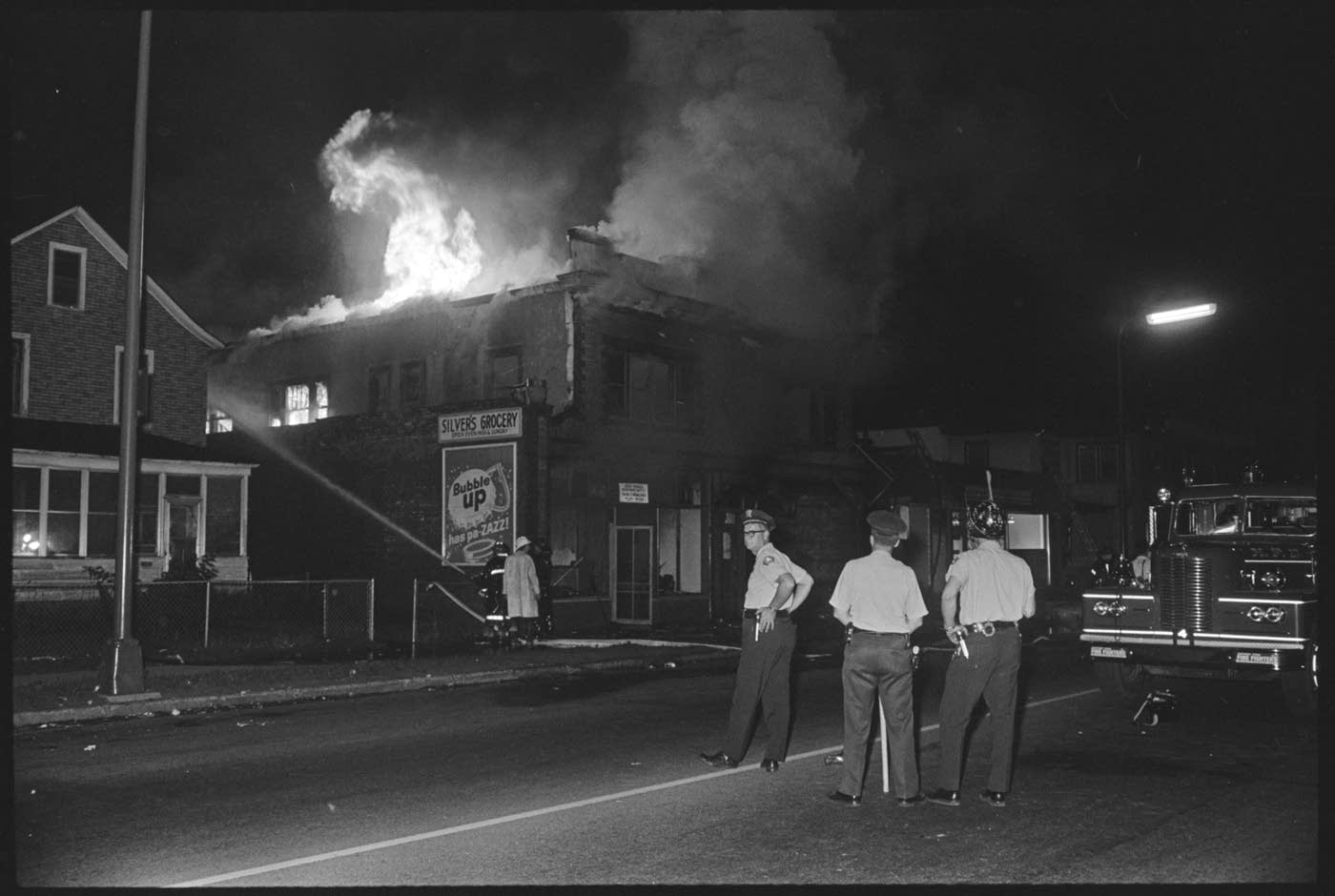

In August 1966, a group of 35-50 Black youths decided to make the owning class on Plymouth Avenue feel their pain, smashing out windows and looting shops. When police arrived “in riot equipment,” they dispersed.

“It took a few rocks and the business men on the avenue had to pay,” Clarence Benford Jr., one of the rebels, told the Minneapolis Star at the time. “Why should we be down all the time? It’s time to rise up and let people know we want something.”

Black youth across the country were feeling the same, and during the “long, hot summer” of 1967, at least 150 riots broke out in urban centers across the country, including North Minneapolis. Nationwide, the rebellions resulted in 83 deaths and tens of millions of dollars in destroyed property. America was paying the price for the systematic exploitation and disenfranchisement of its Black population and those in power were scrambling for a fix.

On July 19, 1967, a group of about 500 young people marched to Plymouth Avenue and systematically attacked, looted and burned businesses with a history of exploitation and violence toward Black people. The historical record is blurry on the exact event that triggered the rebellion — two instances of police brutality and one instance of a Jewish shop owner shooting a young Black man are suggested, all in the short period leading up to the event. The question of which of these events actually triggered the riots only helps illustrate the severity of the racialized oppression at play on the Northside in that time.

According to the FBI, the combatants were Black youths, but Northside residents contended that poor whites and Natives also participated in the uprising. When the cops arrived this time, the rebels fought back, pitching rocks and bottles at them. The subsequent rebellion lasted three days until the National Guard was brought in to squash it. In the end, it caused more than $4 million in damage and led to 26 arrests.

Minneapolis Mayor Arthur Naftalin, the first Jewish mayor of Minneapolis, declared that the summer’s events were “simply a product of lawlessness” and were not “related to deficiencies or neglect.” He summed up the white establishment’s attitude toward urban Black youth: “These people are beyond our reach.”

Decades later, the ghosts of ‘67 would repeatedly come back to haunt the Northside. In 1990, Minneapolis Police fatally shot 17-year-old Tycel Nelson in the back, leading to deep resentments that helped spark a decade of violence in the city that became known as “Murderapolis.” In 2002, after police shot an 11-year-old during a raid on the Northside, the community responded by burning a news van on 26th Avenue North. Just four years later, when police killed Hmong teenager Fong Lee, many Northside residents with no reason to trust the cops believed they’d planted a gun.

In 2015, police killed 24-year-old Jamar Clark on Plymouth Avenue in what some described as a street execution. In response, a Black-led, multi-racial group of Northsiders took the street, declared a “no cop zone,” and established an encampment in front of the Fourth Precinct that lasted 18 days.

Through a process of redlining, over-policing and mass incarceration, North Minneapolis would fall into economic and social disarray over the decades following the 1967 riots, as those in power attempted to push back on the growing Black militancy and increasingly powerful demands for sweeping economic justice.

Coupled with racist crime wave hysteria, this economic disinvestment created an area in which kids like Marvin Haynes had little to hope for. Imprisonment for boys growing up in his neighborhood was a near certainty.

[The parents of Marvin Haynes, Sharon Shipp and Marvin Haynes, Sr., dance together (L) and Marvin at about 8 years old stands with a hat on next to his brother Johnnie (R).]

To the cops who policed the streets Haynes and his friends walked each day, it wasn’t the Northside, it was the Fourth Precinct — a zone of crime and expendable lives. Sgt. Michael Keefe, the lead investigator in the Randy Sherer case, wrote in his swaggering, self-published memoir entitled “Minneapolis Burning” that the Fourth Precinct was the place for tough cops like him.

“I picked the roughest and toughest assignment in Minneapolis, the Fourth Precinct,” Keefe wrote. “I saw it as a challenge, and I loved every minute of it.”

In the fifteen years leading up to the murder of Randy Sherer, the Minnesota legislature increased sentencing for various crimes more than 75 times. Minnesota’s prisons were bursting with young Black and Brown men and the Northside was in rapid decline. In 1980, the poverty rate of the McKinley neighborhood was only 12%. By 2000, a quarter of the households would be living below the poverty line. That number would continue to grow over the next decade.

The economic shift was accompanied by a demographic one, as the same story played out in North Minneapolis that was unfolding in cities all across the country — between 1990 and 2000, the white population of the Northside fell 39%. Masses of Hmong refugees, emigrating primarily from Laos and Thailand, filled the gaps along with Black families in the city, who since the 1920s, were steadily being forced north through the city.

News reports from the early 2000s are filled with coded statements about how the neighborhood around the flower shop was changing; the store is called a “symbol of stability” amid a growing wave of “crime” and “chaos.”

“We had more broken windows and things of that nature,” one of Mannie’s children would later explain. “We had a few of the windows shot out and we never had that years ago, so I mean it just, just a lot more crime in the area…that’s how [the neighborhood] changed.”

Rev. Gallmon remembers that violent crime increased during the period surrounding the flower shop murder. “That was always a burden for me as pastor of a church in that community. It was always a thorn in my side that said to me I wasn’t doing enough or that the church wasn’t doing enough to help with the situation,” Rev. Gallmon told Unicorn Riot. “Even when I left, I left with the feeling somehow that I didn’t do enough to help with some of the senseless murder and killings that were going on in that community.”

Despite these changes, the Sherers continued to open the shop each morning, selling decorative bouquets for birthdays, Mother’s Day, graduation parties, and weddings. And it remained a family affair — Jerry, the owner, would come in most days while his sister Cynthia worked the counter. His brother Randy would hang out, clean up and chat with customers. Other family members, like Cynthia’s daughter, worked there part-time as well.

The morning of Sunday, May 16, 2004 started like any other. Cynthia, who had changed her name to McDermid when she married, entered the flower shop at 8:50 a.m., ten minutes before it was scheduled to open. Her daughter had been scheduled to open that morning but had asked her mother to fill in so she could spend time with her kids.

Jerry came in early that morning and stayed until about 11 a.m. when he asked his brother Randy to come in. The family had a rule that no less than two employees would be present in the store at a time. So Randy joined his sister at the shop, chatting, sweeping and helping out where he could.

Sometime between 11:30 a.m. and 11:45 a.m., a young man entered the shop and asked about a bouquet of flowers. McDermid thought she had seen him before. He’d been in the shop four or five times, she would later claim — making change or, around Valentine’s Day, purchasing flowers. He was about 5 foot 10 or 11 inches tall, and in his early 20s.

The two made small talk. He said he needed some flowers for his mother’s birthday. That his mother was a chiropractor. “He spoke with clarity,” McDermid would later tell police. “It was not a hip-hop type speaking.” He was polite and seemed “educated.”

McDermid showed him a vase of flowers in the cooler near the door. He wanted something bigger, with more flowers in it. Something “real big and showy.” She said she would add some more roses and brought the vase over to the prep table.

“It will be about $40 or $50,” she told him. He said that was fine and that he would pay with his Visa card. The man turned to pick a birthday card off the racks in the lobby. He spun the rack casually, picked one, and handed it to McDermid.

“I picked up a card stick and put it in the vase of flowers,” McDermid recalled. “I glanced up at him. He had a gun pointed about 4 inches away from my face.”

“I’m not joking with you,” the man said. “I want the money.”

McDermid described the gun as having “a chamber where you could see the bullets in it. A round chamber that was down below the handle.” He was holding the gun with two hands.

McDermid took a step to her right, reaching for the cash register, but the man stopped her. “No till. I want the money in the back,” he said. “I want the money that’s hidden here.”

Hearing the commotion, Randy came up from the back of the store. “What the fuck is going on here?” he demanded.

The gunman moved the pistol from McDermid to her brother. When he did, McDermid turned and ran through the back of the building. “As I got to the first doorway I heard the first shot,” McDermid told police. “I got to the back doorway. I unlatched it. It was locked. I heard the second shot. I started running out the door.”

McDermid hopped a fence and banged on the door of her neighbor Etta McCabe, a woman in her late 50s who she had never met. She would later tell the police that as she ran out the door, she glanced into the backyard of the flower shop, into the alley behind the building, and saw the shooter walking north up the alley.

When asked to describe the shooter again, McDermid said his hair was “close cropped. It wouldn’t be bald. Natural.” She said he didn’t have any facial hair.

At her neighbor’s house, McDermid dialed 911:*

Dispatch: Minneapolis Police and Fire. Minneapolis Police may I help you?... Etta McCabe: Yes this is a, a, somebody just robbed the flower shop on Lyndale and 33rd and the owner's right here. Cynthia McDermid: Hello. Dispatch: What's happening? Cynthia McDermid: Uh, listen, get an ambulance right away. I ran out the back door. Dispatch: Okay, who got shot? Cynthia McDermid: My brother is in there.

The dispatcher tried to keep McDermid calm and asked for a description of the shooter.

Cynthia McDermid: One guy, he, he is an African American, about 22 and he's real dark. He had a hat, he had a hood, hooded sweatshirt and he ran down the alley behind the shop. Oh please hurry up. Dispatch: Okay, police already have the call. Cynthia McDermid: Okay. Dispatch: They're on the way. Cynthia McDermid: Alright. Dispatch: You remember it was a black male? Cynthia McDermid: Yeah. Hurry up. Oh man. Dispatch: They're driving there. And he's wearing what? Cynthia McDermid: Uh, he had a, like a hooded sweatshirt. Dispatch: What color? Cynthia McDermid: I don't know. You'll just have to wait until I calm down. I don't know. Oh please. Okay I gotta go. Dispatch: He ran down the alley? Did he have a gun? Cynthia McDermid: Yeah a big gun. He shot my brother

At approximately 11:51 a.m., Officers Rollins and Smelter got a call for available units to report to 3300 Lyndale Ave N in response to a “robbery of business” with shots fired. When they pulled up in front of Jerry’s Flower Shop, McDermid ran out of the shop, where she had returned to check on her brother. She told them her brother was inside and that he had been shot.

When they entered the building they found Randy Sherer, age 55, lying in a pool of blood.

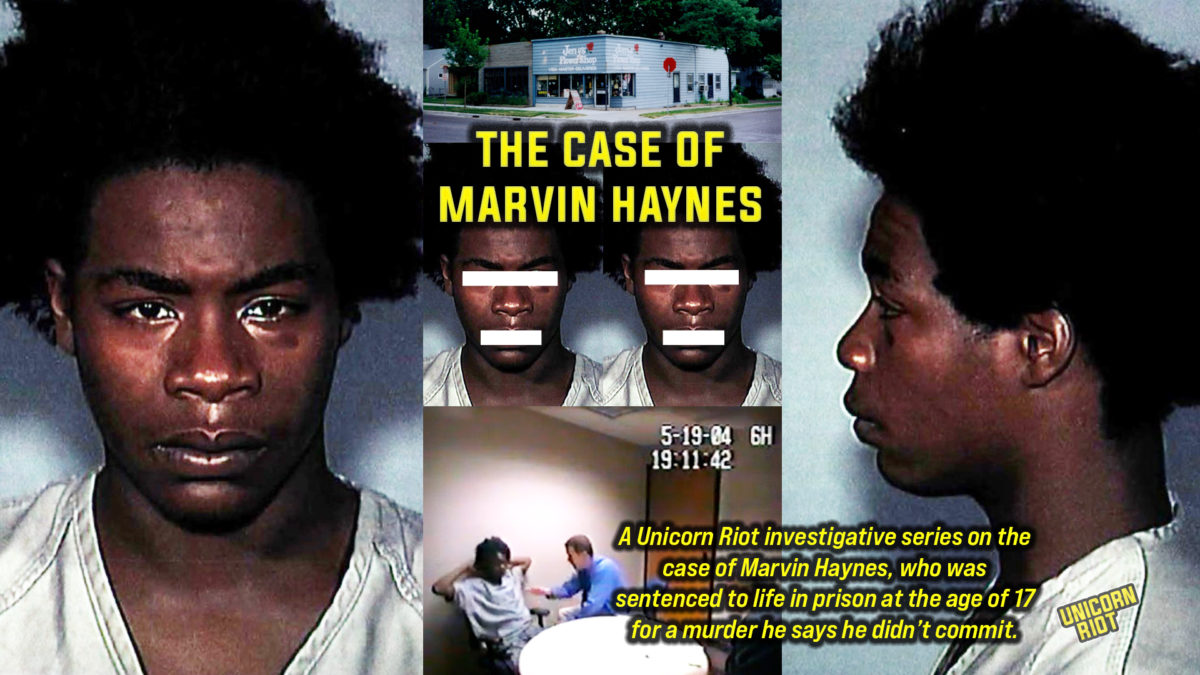

This is the second article in an ongoing investigation looking at the case of Marvin Haynes. Check out the first article here. In our next article, we’ll look at the investigation of the murder of Randy Sherer, or, the frame-up of Marvin Haynes.

*This 911 call transcript was created by the Minneapolis Police Department. Unicorn Riot shortened it and edited it lightly for clarity only. Read the full transcript here.

911-Call-Transcript-MHEditor’s Note and Additional Resources

This article touches on many aspects of North Minneapolis, including some of the rich history of the Northside and some of the police killings there. This is not, by any means, an exhaustive account of the happenings, but attempts to bring context to the general feel of the area in which Marvin Haynes grew up and where Randy Sherer was killed. For a small list of additional resources and media, see below:

“The Way Opportunities Unlimited, Inc.”: A Movement for Black Equality in Minneapolis, MN 1966-1970 [pdf] [Camille Venee Maddox – Dissertation – Emory University] (2013)

Overcoming: The Autobiography of W. Harry Davis [Harry Davis] (2002)

For a Moment We Had the Way [Rolland Robinson] (2006)

Cornerstones: A History Of North Minneapolis 56m 50s [TPT] (2017)

1967 Special Report: Minneapolis Race Riots 25m 03s [ABC Documentary Published by Hezakya Newz] (1967)

Fong Lee: The Story of Tragedy and Injustice 6m 12s [MySPNN] (2012)

Minnesota African American Museum Showcases Black History [Unicorn Riot] (2019)

Historic Black Lives Matter Mural Painted in Minneapolis [Unicorn Riot] (2020)

The Caldwells: Father-Son Duo Team Up on a Portion of Historic Minneapolis Mural [Unicorn Riot] (2020)

Unicorn Riot archive coverage of Minneapolis Police killings in North Minneapolis of Jamar Clark, Thurman Blevins, and Travis Jordan.

Niko Georgiades contributed to this report for Unicorn Riot.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization:

The post The Case of Marvin Haynes – Part Two: The Murder of Randy Sherer appeared first on UNICORN RIOT.

by Unicorn Riot via UNICORN RIOT

No comments:

Post a Comment