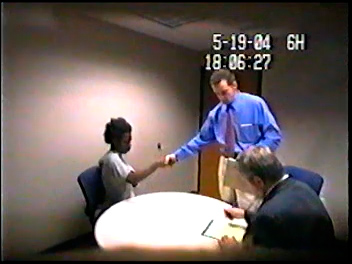

Minneapolis, MN – The grainy surveillance camera footage shows a small interrogation room—fifteen-by-fifteen, white walls, short cut-pile dark carpet, circular table, and a blue swivel chair. A door on the far wall stands open to the hallways and cubicles beyond. The date in the corner of the video reads 5-19-04. A counter clicks off the seconds.

A bland-looking cop in a gray suit walks in and directs a young man to the chair. The officer removes his handcuffs.

The kid sits down. As the door closes, he pulls his arms into his short-sleeved shirt against the cold of the air conditioning. He’s 16-years-old, 5 feet 7 inches tall, 130 pounds. He’s Black, and he wears a 4 inch Afro, a light blue jail-issue smock, and loose pants of coarse cotton.

He doesn’t know it yet, but in a little over a year, he’ll be sentenced to spend the rest of his life in a prison cell for the murder of Randy Sherer, a white man he says he’s never seen before. A jury will convict him without a shred of physical evidence linking him to the murder.

The kid stares at the wall. He yawns. After a couple minutes, he puts his head down on the laminate surface of the table. He doesn’t look worried. He looks bored.

Five minutes pass. Then seven. Finally the door opens. A white man with gray hair enters the room, wearing a suit. “Hello sir,” he says. A second white cop follows him in.

“How you doin?” the kid responds. “Ey, I didn’t get no receipt that they took my money down to the what’s-its-name,” the kid tells him. He speaks quickly, mumbling, his words difficult to discern.

“I’m sorry?” the man asks. The kid repeats himself, concerned about the small amount of cash the police took from him when they booked him into jail that morning.

“I’m Sergeant Keefe, this is Sergeant Mattson. Your name is what, Marvin? What do you go by, Marvin?”

“Marvin. Little Marvin,” the kid responds. They shake hands.

About six hours before the video starts, Marvin Haynes was picked up by police and told he was being arrested for failure to appear in juvenile court on a previous charge. He was taken to the Hennepin County Juvenile Detention Center before being transported to Room 108 in the Minneapolis Police Headquarters at City Hall for interrogation.

The police read Marvin his Miranda Rights. They tell him he has the right to an attorney.

“I want to have my mom down here,” he responds. The police brush him off, asking whether his mother is a lawyer. During the interrogation, he asks for his mother at least eight times, but the police carry on, sometimes saying they can’t get a hold of her, other times ignoring him entirely.

Seated across the table, the officers ask Marvin about the warrant he was picked up for. He explains that he was trying to get down to court, but he couldn’t make it. He says his mom tried to reschedule it for him, but her phone was turned off. His tone is casual, like he’s trying to clear up a procedural matter.

The officers ask Marvin where he was that weekend. He tells them he was with his cousin Poopy, he was with his girl Muffy, he was trying to get Dee Dee to braid his hair. He slept in until three in the afternoon on Sunday because he was out late with friends Saturday night. He yawns and leans way back in his chair, stretching as he talks. The interrogation continues.

“Do you own any guns at all,” Sgt. Mattson asks.

“No, I don’t own no guns,” Marvin replies.

“We’re investigating an event that happened over in this flower shop off of Glendale, a little bit north of Lowry. You ever been in that flower shop at all?”

“Flower shop? What flower shop,” Marvin asks.

“It’s called Jerry’s Flower Shop…You know Lowry and Lyndale?”

They discuss the cross streets, cardinal directions.

“I ain’t never been in that flower shop,” Marvin responds. “I thought you were talking about Penn ‘cause there’s, like, a flower shop on Penn.”

The police watch Marvin intently when they bring up the flower shop, gauging his reaction. They ask him if he’s seen anything in the news, and he mentions a bus accident he heard about. They prod him, asking how he gets money. Does he have a job?

“No, I get money from girls. All kinds of girls give me money.”

“Why do girls give you money?”

“I don’t know, ‘cause I got it like that,” Marvin says, with a cocky teenage smile. The cops watch him, their faces stern. Did he really just brag about getting girls in the middle of a murder interrogation? Is he a skilled liar or a dumb kid who doesn’t know what’s going on?

Fast forward two-and-a-half hours. Marvin is still in the room, but the scene has changed. Marvin, sobbing, sits in the corner, pulling his shirt up to wipe his tears and running nose. The men are screaming and pointing at him. Their faces contort with the effort. They’ve been lying to Marvin, saying his fingerprints and DNA have been found at the murder scene, that video cameras recorded him entering and exiting the store. They tell him they’re charging him with murder.

“You went in there, trying to look like a hardcore ass and you didn’t get what you wanted so you turned around and you said ‘fuck it, I’m gonna shoot this guy,’” shouts Keefe.

“My mom got money, I can get money any time I don’t need to ask nobody,” Marvin shouts back.

“The old lady wouldn’t give you money, so you said ‘fuck it, I’m gonna shoot him.’”

Finally, Marvin swallows his tears. His voice becomes defiant. “OK. Charge me with it then,” Marvin says. “And guess what, y’all gonna be wrong and I’m gonna get out.”

“The hell we are,” Keefe responds. They keep shouting at each other.

The cops get up to leave the room. “I got nothing to say to you. You shot that guy because you were pissed off because you didn’t get your money!”

“Y’all got the wrong person! I got money. I got money,” Marvin shouts as they leave.

“I ain’t never did nothing,” Marvin yells through the door. “Y’all can’t charge me with shit. The fuck. I’m only 16. Y’all better get the fuck out of here with that.”

The tape clicks on for another fifteen minutes as Marvin paces. After a while, he gets up and knocks at the door. He’s been in this room for nearly three hours.

As he paces, the cops are raiding his home where he lives with his mother and sisters. Officers are digging through his room, searching for guns, confiscating hoodies and gym pants, interrogating his mother, asking his sisters Marvina and Lakiesha when they saw Marvin that weekend. They bring in dogs to sniff the yard for evidence. They impound his mother’s car, a red Ford Taurus, to the forensic yard pending a search warrant.

Meanwhile, back in interrogation room 108, Marvin eventually gets up and stands near the door. He puts his hand on the lightswitch, and the room goes black. Marvin appears again, the room awash with fluorescent white light. Marvin’s hand is still on the switch.

Again, the room falls into darkness and the tape cuts to static. The scene is over.

Eighteen years later, Marvin’s side of the story has not changed much from that day in the interrogation room, although now he tells it in the voice of a much older man. From his prison cell at the Stillwater Correctional Facility on the Minnesota-Wisconsin border, Marvin has not stopped professing his innocence in the shooting death of Randy Sherer at Jerry’s Flower Shop on May 16, 2004.

People are finally starting to listen.

Watch the Minneapolis Police video of their interrogation of then 16-year-old Marvin Haynes on May 19, 2004 in Minneapolis Police Headquarters in City Hall.

On September 2, 2005, at 6:19 p.m., 15 months after the murder of Randy Sherer, a jury unanimously found Marvin Haynes guilty of murder in the first degree after only six hours of deliberation. Their decision relied heavily upon the testimony of a handful of witnesses between the ages of 14 and 17, none of whom had witnessed the murder and three of whom have since recanted their testimony, saying they were threatened and pressured by police to lie.

The only eyewitness, flower shop cashier Cindy McDermid, initially described a man who seemed “to have an education,” who was much taller and older than Marvin–a short, baby-faced kid who could hardly read and had dropped out of remedial school before he was arrested. During photo arrays and line-ups rife with procedural violations, McDermid first identified another kid as the shooter before settling on Haynes.

The murder investigation was led by Sergeants Mike Keefe and David Mattson of the Minneapolis Police Department. Sgt. Keefe, who was promoted to lieutenant three years later before being demoted again, has a long and documented history riddled with accusations of inappropriate, racist, and unprofessional behavior in his role as a law enforcement officer. A 2020 report investigating the high-profile wrongful conviction of Myon Burrell in Minneapolis accused Keefe of “tunnel vision” and “confirmation bias,” explained as a “disinclination to seek evidence that can disconfirm [one’s] beliefs.”

Nonetheless, in late September 2005, Marvin Haynes was sentenced to life in prison at the age of 17.

Haynes’ public defender unsuccessfully appealed some aspects of his trial to the Minnesota Supreme Court, which has jurisdiction over all appeals in first degree murder cases. The Court affirmed his conviction, issuing a thirteen-page opinion disagreeing with Haynes’ attorney about the procedural issues they’d objected to.

Over 18 years have passed since Haynes was initially arrested, every day of which he’s spent in state custody.

The case of Marvin Haynes stands as an historical precursor to the events of 2020 in Minneapolis, from the murder of George Floyd to the burning of the third precinct, which laid bare the city’s violent and racist foundations. In April, 2022, a damning report by the Minnesota Department of Human Rights officially stated what the city’s overpoliced and heavily incarcerated underclass had been saying for decades–Minneapolis cops are a racist, violent, paramilitary force that routinely act outside the law with impunity.

In late 2022, the Great North Innocence Project agreed to review Haynes’ case and in early January of this year, they issued a report to Minnesota’s Conviction Review Unit, calling for Haynes to be fully exonerated.

“Marvin Haynes is innocent of the crimes for which he was convicted,” wrote Innocence Project attorney Andrew Markquart in the report. “The interests of justice demand that he should be fully exonerated and released from prison as soon as possible.”

The Conviction Review Unit, known as the CRU, was formed in 2021 as a partnership between Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison’s Office and the Great North Innocence Project. It is one of 96 such conviction review units currently operating in the country, but one of only four that are run by the state’s attorney general’s office.

The CRU was formed in the wake of the Myon Burrell case, which brought national attention to wrongful convictions, juvenile life sentences, and racial bias among police, judges and juries in Minneapolis. Haynes was arrested just two years after Burrell, amidst the same era of tough-on-crime panic, and the two cases bear many similarities.

The Innocence Project is calling for the CRU to consider Haynes’ case. If the CRU decides to intervene, they will make a recommendation to the Minnesota Attorney General, Keith Ellison, who makes the final decision in the CRU process.

Since Haynes was convicted by the Hennepin County Attorney’s Office, newly elected progressive prosecutor Mary Moriarty will also be involved in the process. After decades of service as a public defender, the Haynes case may be one of the first opportunities for voters to test her on her progressive platform as a prosecutor.

Unicorn Riot conducted interviews and reviewed thousands of pages of court documents, trial transcripts and police reports in the course of our investigation into Haynes’ case. Those documents and conversations revealed a pattern of police coercing teenage witnesses, an investigation completely lacking physical evidence linking Haynes to the scene, repeated violations of police eyewitness identification procedures, and an overall pattern of racial bias.

In the midst of our investigation, one of the state’s key witnesses, Marvin’s younger cousin Isiah Harper, admitted to lying about Marvin’s guilt at trial. Harper, who was only 14 at the time of the murder, told Unicorn Riot that cops got him to say what they wanted him to say by threatening him with decades behind bars. They continued to coerce his testimony despite him telling judges and juries repeatedly that he was lying and that the police had made the story up.

In this series, we’ll walk you through the case of Marvin Haynes—from the murder of Randy Sherer at Jerry’s Flower Shop in Minneapolis’ Northside, to the ensuing investigation and trial. Along the way, we’ll talk to witnesses, family members, community activists, ex-cops, and politicians about the case and the broader context in which it unfolded—the tough-on-crime era that packed the nation’s prisons with disproportionate numbers of Black and Brown people, and the ruthless reign of Amy Klobuchar as Hennepin County Attorney.

This is the first article in an ongoing investigation looking at the case of Marvin Haynes. Stay tuned for our next article, where we’ll take a close look at the murder of Randy Sherer and the context of the economic abandonment of Minneapolis’ Northside in which it occurred.

Niko Georgiades contributed graphics to this report for Unicorn Riot.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization:

The post The Case of Marvin Haynes – Part One appeared first on UNICORN RIOT.

by Unicorn Riot via UNICORN RIOT

No comments:

Post a Comment